Type 1 Diabetes and Ultra Endurance Sport – Insulin Dosing.

All material on this website is provided for your information only and may not be construed as medical advice or instruction. No action or inaction should be taken based solely on the contents of this information; instead, readers should consult appropriate health professionals on any matter relating to their health and well-being.

A few other Type 1 diabetics have messaged me on the blog asking how I managed my insulin on the Great Divide Mountain Bike Race. Certainly it is agreed that “everyone is different” when it comes to insulin dosing – but I do wish that I could have found a frame of reference online that would have helped give me an idea of how insulin works in conjunction with ultra-endurance cycling and the associated stress.1 In this post, I intend to summarize my insulin management to give readers a rough idea of what to expect (at least based on this n=1 experiment). I’ve also been approached by many non-diabetics with questions about low carbohydrate diets. The information I plan to provide here indeed has some relevance to non-diabetic athletes as well. As you will see, keeping your insulin and glucose levels low (and steady) has a host of benefits in terms of performance during ultra endurance events, regardless of whether or not you’re a diabetic.

I like to say that I have a “magical power” when it comes to conducting nutrition experiments. The magical power is that unlike non-diabetics, I know how much insulin is active in my body. I know this because I’m the one who put the insulin in there. When people see me poke my finger and draw a blood sample, they often ask, “How are your insulin levels?” The thing is: I’m not measuring my insulin; I’m actually measuring my blood glucose levels. Currently, there is not a portable, inexpensive device for testing your insulin levels. In spite of that, I always know how much insulin is in my body at any given moment – because I injected it. I keep track of the timing of my injections with an app on my phone so I can estimate how much insulin is still active.

Prior to the race, I spent about 6 months conducting experiments to see how my body would respond to different exercise intensities and durations in combination with various foods, insulin dosing, and timings. For example, I’d drive my car to the base of a local hill, fill my pockets with glucose tablets and test strips, take an injection of Novolog/Humalog, set a timer and do a 5 minute sprint up the hill. I had to conduct these experiments over multiple days because once the insulin is injected, it’s in there for 4+ hours. In each experiment, I’d delay a different amount of time trying to see if I gained any performance advantage from having my insulin “peaking” for high intensity efforts.2 Besides doing high intensity experiments, I also experimented with endurance dosing. For endurance, I would experiment on long, steady bike rides with progressively lower doses of Lantus (and no Humalog or Novolog). My findings are the following:

- The best combination of diet/insulin/exercise for long term health is not the same as the best combination for performance.

- Personally, I’ve not found a way to eke out higher performance during high intensity efforts by using rapid acting insulin + carbs. I don’t understand why this is, but I will discuss the results in a different post.

Insulin and exercise for long term health

As mentioned above, I believe that the best regime for long term health in a type 1 diabetic is somewhat at odds with the regime necessary for high performance (**This is my opinion based on my research and experimentation.**) From the research, it is pretty clear that minimizing your standard deviation (i.e. fluctuations in glucose levels) is very important in minimizing diabetic complications and improving long term outcomes3. Similarly, the best long term outcomes for non-diabetics occur when blood sugars are maintained in the normal range (average blood glucose of ~83-103mg/dL).456 You probably don’t have time to read my citations, but I have grabbed graphs from three additional research papers and shown them below. As you can see, there is a lot of research on non-diabetics in this realm – and it all agrees (plus or minus 0.5%) that optimal A1c is around 4.5 – 5.2% – which corresponds to an average blood glucose of 83-103mg/dL.

- Oft cited chart of relationship between Hemoglobin A1c and various

- Taken from this research: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/132/4/269

- Taken from: http://circoutcomes.ahajournals.org/content/3/6/661.figures-only

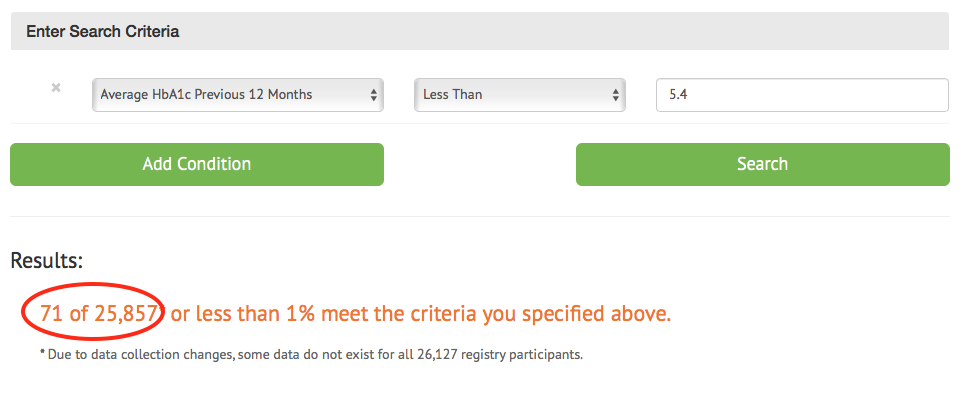

These studies are on non-diabetics. Of course, the recommended A1c for type 1 diabetics is much higher based on the research. Unfortunately, the research on type 1 diabetics doesn’t include normal blood sugars; there aren’t any studies on the outcomes of diabetics maintaining normal blood sugars – probably because almost no type 1 diabetics actually achieve normal glucose averages.7 For example, I’ll find articles titled Explaining the increased mortality in type 1 diabetes – only to find that the lowest A1c “bucket” is 6.9%! (by the way, that was the best bucket to be in, but I’m not certain that we need to start explaining increased mortality until we start studying diabetics who maintain normal glucose readings). In a database of type 1 diabetics, you can search for conditions such as last A1c (which is a measure that correlates with your average glucose for the past 3 months), and you will find that only a tiny fraction of a percent of type 1 diabetics have A1c’s in the normal range of 4.2%-5.4%. Therefore, it is a very difficult group to study. Check out what happens when I search the database for the number of type 1 diabetics who maintain a normal A1c:

71 out of 25,857 – Only 0.27% of type 1 diabetics maintain normal blood sugars.

Based on my findings above, I am striving for an A1c in the 5% range, with a minimal standard deviation.

Challenges in balancing health and performance

The problem with trying to perform at a high level athletically is that you induce dramatic blood glucose variations, which as stated above are detrimental for long term health. As you can see from the graphs above, spending too much time in the low range can be just a detrimental as spending too much time running high. Besides that, there are always the acute risks of hypoglycemia (coma/seizures/death) and hyperglcyemia (ketoacidosis) – both of which are a lot more likely to occur with short notice when you’re exercising.

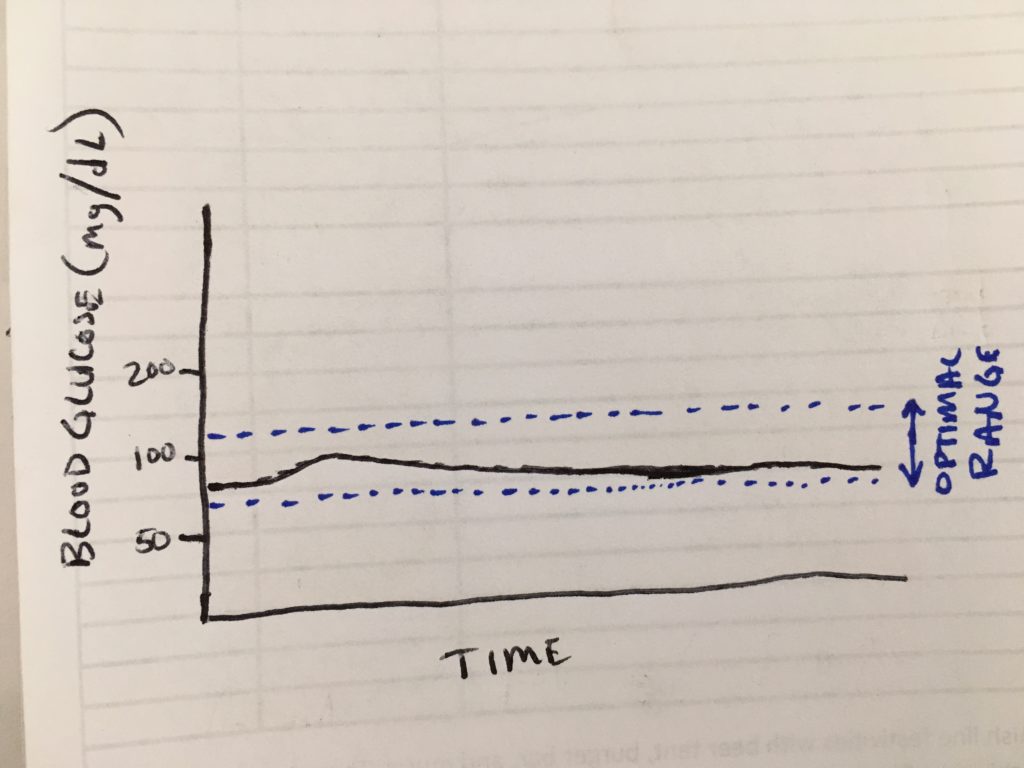

The blood glucose profile that I aim for while exercising for health looks approximately like this:

Target blood glucose graph for endurance exercise. NOT high performance.

To achieve this, I rely almost exclusively on Lantus and minimal caloric intake before and during exercise. Here is a rough breakdown of what I do (remember, every day is different):

To begin with, I have become accustomed to eating a low carbohydrate diet. I’ll discuss the diet more in another post, but if I average out my macro nutrients from the days I weigh my food, it comes out to about 80% Fat, 15% protein, and 5% carbohydrate. Being accustomed to this type of diet makes the next part much easier: Riding without eating. If the exercise is in the morning, I will simply skip breakfast. This has a host of benefits (like encouraging my body to utilize fat stores as opposed to glycogen) – but it also allows me to use less insulin – and omit the morning meal-time dose. This is a HUGE boon for exercise because the rapid, somewhat unpredictable action of Novolog causes severe fluctuations in my blood sugar, depending on how active it is at any give moment. Exercise exacerbates the problem too. For example, if it is hot out, the skin absorbs the Novolog more quickly. If you’re going hard, your digestion slows meaning the Novolog may out-pace the appearance of glucose in your blood stream; this makes it harder to get the timing right. If it is warm and you sweat, changing hydration levels dramatically affect the insulin absorption rate meaning that you don’t know when it is going to peak.

People may wonder: How do I achieve a relatively flat line glucose while exercising? One part is the adaptation to fat burning mentioned above. The other part is to becoming a Lantus dosing ninja. I do not always nail it, but in doing all of my experiments, I found that my Lantus dose is not just dependent on today’s exercise, but also the previous ~3 days of exercise. So, for example, if I’ve been going on long rides for 3 days in a row, I’ll need to use less Lantus to maintain this flat line compared to a situation where I’ve been sitting on the couch the 3 days prior. A rough example would be this:

3 days on the couch – then go for a long ride: 12U Lantus.

Riding 2 days in a row, then embarking on the 3rd long ride: 8U Lantus

I’ll also do anything in between. For example, if the 2 days prior had been farily easy, maybe I’ll shoot 10U or 11U Lantus.

These dosages may seem small for a 175lb guy – but if I go on a long drive and chill out with family for a few sedentary days, I’ll have to dose 24U+ Lantus just to wake up with a glucose under 100mg/dL. This dose is about average for someone of my weight, age, and body composition. I mention this so it’s clear that I don’t have an unusually high insulin sensitivity in the absence of exercise.

The Lantus dosing is just part of the equation. How I fuel is also important in order to make this work. Usually for the first 2-3 hours, I can ride along with no food at all. If I’m on a lower dose of Lantus (maybe 6U or 7U), I can probably ride for hours without food or significant weakness. Under these very low insulin/glucose (70-85mg/dL) circumstances, I can just keep riding… but I’m not going to have a ton of power for high performance efforts. If I’m taking a little higher level of Lantus (say 8U-10U), then I’ll probably need to eat after 2-3 hours have elapsed. By fueling with very LOW or SLOW carbohydrate fuels, I can continue to ride without a huge aberation in my blood glucose levels. Easy to carry, low carbohydrate fuels that energize and promote stability for me are foods like cheese, almonds, pecans. Carbohydrate contiaing foods are slightly more risky, but I’ve found a few foods that absorb so slowly and evenly that they almost behave like low carbohydrate fuels. Examples are: Raw potato8, small amounts of refried beans or hummus. The last two foods will only work while exercising – if not exercising, a Novolog dose will be needed.

After the ride, it will be necessary to refuel. I’ll do so with a normal, low carb meal combined with a (usually reduced) amount of Novolog. When inactive, my I:C ratio is usually about 1:10… but post exercise, I count on an I:C ratio of 1:30. Sometimes, I’ll dose with an I:C ratio of 1:50, and then follow up with a correction dose later (if necessary). I must take GREAT CARE not to exercise again (however lightly, including a short walk) during the 3-4 hours after I give myself the Novolog injection. This has been the mistake I’ve made most often, and it has laid me very low. Even something as light as a short walk, gardening, or climbing a short staircase under these conditions can mess up the calculation and ruin the next half hour with severe hypoglycemia.

Insulin and exercise for high performance / racing

You may have noticed above that I mentioned that I’m not going to have a ton of power for high performance efforts utilizing the “healthy” strategy. Although low-carb fan boys will argue that their low-carb diet is the key to their performance, I haven’t found this to be the case during the actual effort (we’re talking top end performance here). What I’ve found is that maintaining a very low carbohydrate diet during the training season is the perfect adjunct to using a moderate carbohydrate approach during racing. The low carb approach helps the body adapt to the low carbohydrate environment (and makes it so I’m much less reliant on carbohydrate) – but supplementing in carbs enhances my performance when needed. To put this in perspective, I generally eat about 30-50g of digestible carbs in my daily life. During the Tour Divide, I ate (an estimated) 1,000g of carbohydrate per day. That is 2.2 pounds of sugar (or what would soon become sugar once it hit my digestive system). That may seem like a ton of sugar, but if you consider that 1,000g of carbohydrate is 4,000 calories – and I was probably eating 12,000 calories per day… that means that the carbs were actually only about a third of my total calories.

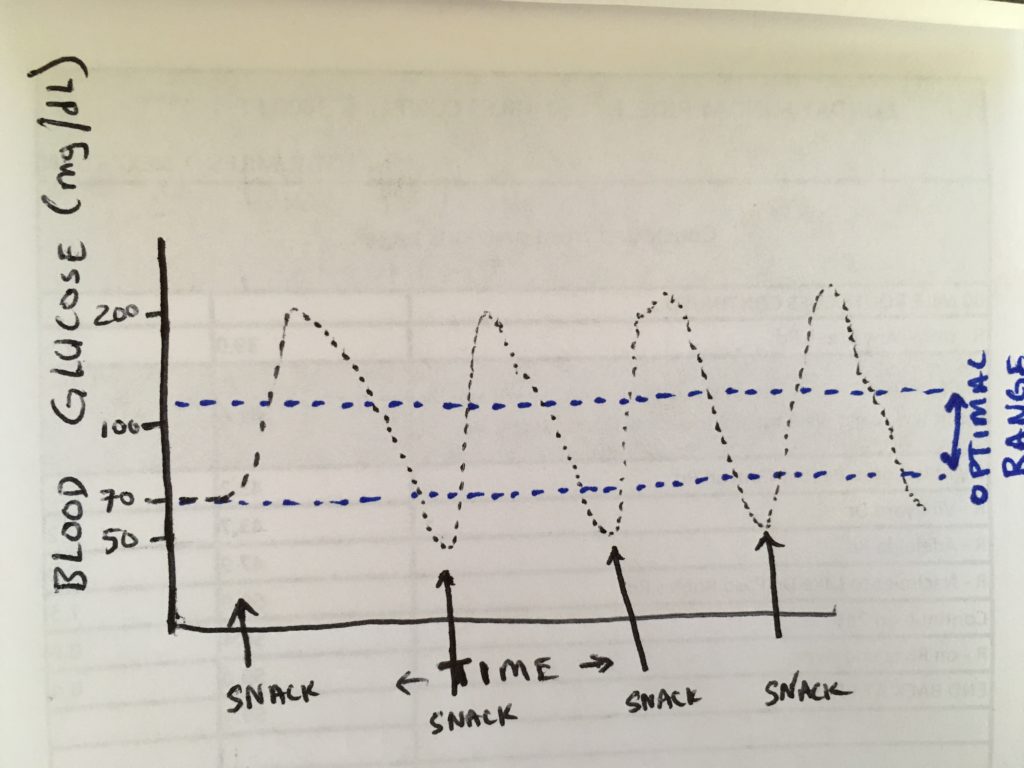

There are probably many ways to do this in racing, but the blood glucose management strategy I employed during the Tour Divide looked like this:

Blood Glucose Strategy employed during the Tour Divide

This glucose profile isn’t optimal for health, and you may be wondering why I did not use a pump to optimize my insulin delivery (I explain that in another post). Even though this glucose profile was sub-optimal, I believe it ended up saving me time during the race. Here is how it worked:

Remember above, I said that I figured out the amount of Lantus needed to maintain a flat line? Under the “performance strategy,” I overdose the Lantus slightly – by about 30%. This means that during exercise, I’ll be constantly falling instead of maintaining a flat line. During the race, I would be riding continually for about 18-19 hours, so my glucose consumption would be somewhat predictable (downhill sections non-withstanding). The reason I overdosed the Lantus was so that I could get the performance enhancing benefit of carbohydrate without the need to pull over and inject Novolog each time I wanted to eat. Besides saving time on the Novolog injections, Lantus provides a slower (safer) decline when combined with exercise – it’s slow enough that I have time to balance it out with food. During the race, I maintained my hypoglycemia awareness, so the second I felt any shakiness or hypoglycemic symptoms coming on, I would eat ~30g carb. This would send my blood sugar skyrocketing into the mid 200s (perhaps a necessary evil). I’d continue to ride until I felt the first hint of symptoms again, and hit it with the sugar once again. This is actually probably very similar to how most non-diabetics ride (minus the upper excursions to 200mg/dL, and the fact that that their pancreas turns off their insulin when they start to get low).9. Because of the internal regulation that non-diabetics have, they make a gradual slide as they approach lower blood sugars whereas I continue to plummet. This is because for me, there is no turning off the Lantus which acts for 18-24 hours.

At the end of the day, I would still try to eat fairly low carb, but it was mostly at this time that I would utilize Novolog. I would stop to sleep for about 4 hours meaning that I could eat a decent last meal prior to sleeping and the Novolog would help me absorb those calories w/o the risk of exercise induced hypoglycemia. I’d keep my dosage low and any time I woke up during the 4 hour nap, I’d test my glucose to see if I needed to make a correction. I would generally under-dose the Novolog at these times, and run an unhealthy, higher blood sugar at night. I chose to do this for safety given the remoteness of the journey. Under controlled circumstances such as being at home, I would not allow this to pass. The four hour activity of the Novolog more-or-less matched my sleep patterns in that it would be wearing off about the time I woke up. Before the race, I had an A1c of 4.9%. After the race, I tested at 5.6%

…and about the gas station food

Everyone asks me, “What did you eat!?” You don’t exactly encounter a good selection of food in the remote locations along the Tour Divide. Here is a rough idea of the foods I would often seek out at the Gas-Station-type places along the route. These are all products that I regularly encountered along the route in 2017. The popularity of various products will probably change over the years, but this is what worked for me:

Low Carbohydrate Sources

- Think Thin Bars – These hardly spike me at all. They have a pretty high carb content, but because they are mostly sugar alcohols, they prevented me from spiking over 200 when consumed in moderation at the correct intervals.

- Pure Protein Bars – These are not very spiky for me – the carb count is high, but it is from sugar alcohols, so about 1/2 the potency of normal carb.

- Muscle Milk – Muscle Milk has all sorts of flavors, but ONLY ONE OF THEM is low carb: banana. Banana is 8g carb with 5g fiber, for a net carb of 3g! Combine that with 40g protein in the pro series, and you have a pretty good fuel.

- Quest Bar (Raspberry) – These bars are more spikey than the 5g net carb on the label would suggest. Nevertheless, my blood glucose is less affected than by some of the higher carbohydrate bars listed below

- Avocados (found in some gas stations)

- Canned Tuna

- Canned Sardines

- Steak (consumed 3x at sit-down restaurants along the way).

- Blocks of cheese (I’d eat a lot of these, and they pack fairly well)

- Almonds / Pecans

- Diet Soda (for me, really just a treat as they have no nutritional value). Diet Pepsi has the lowest caffeine of the colas. 7up and Sprite have none.

Higher Carbohydrate Sources

- Cliff Builder Bars – These will spike the glucose more, but have enough fat, fiber, and protein to slow it down.

- Met-RX bars – These have a pretty massive protein content – which seems to slow down the very high carbohydrate content. To make these work, however, I would not eat an entire bar at once (otherwise, it would be too spiky). I would try and make it last over the course of 30 minutes.

- Supreme Protein Bars – These bars spiked me even more than the Met-Rx bars. A couple times, these sent me quite high in spite of continual exercising. I would also try to spread their usage out over a period of time

- Gatorade Bars – Although these are touted as protein bars with 20g of protein, they are VERY spikey. In fact, after I discovered my response to this product, I decided to always keep a couple on-hand for emergencies. These bars produce a rapid rise in blood glucose that could be helpful in the event of a hypo. They’re almost as good as a glucose tablet!

- Muffins – enough fat and fiber, and they will absorb a little more evenly.

- Peanuts (these are moderate carb. In fact, they could even be listed in the low carb table above).

- Pre-packaged Sandwiches with meat (These don’t pack well and cause highly variable blood glucose results, so I’d mostly avoid them)

*Disclosure: The links above are affiliate links. If you appreciate the info I’m providing and are interested in any of these products, consider purchaing via my links, as I receive a small comission. These links go to the specific products that I have direct experience with. There are a zillion other products, but these are the few that I have vetted out because they commonly appeared along the route.

References & Footnotes

- Note: I have been in touch with Chris Williams from Team Novo Nordisk and Joanne Southerland (Mother of Phil Southerland who started Team Type 1) – but they informed me that their contract with Novo Nordisk strictly prohibits them from discussing how they manage their diabetes. Clearly, type 1 diabetes treatment is different for everyone, but in everything I do, I benefit from learning from others, which is why I’m sharing this information as “educational” – NOT as advice

- Note: Quite a few people have made comments (perhaps jokingly) that I’m using performance enhancing drugs, or that I have an advantage by injecting insulin. I even stepped into a conversation once where I overheard someone saying that she thought that I had “cheated.” This is a total fallacy. Type 1 diabetes is NOT a performance advantage. I’m having to manually accomplish what a non-diabetic pancreas does on autopilot.

- Reference: Is reducing variability of blood glucose the real but hidden target of intensive insulin therapy?, Moritoki Egi, Rinaldo Bellomo, and Michael C Reade, 2009, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2689479/

- Reference: Hemoglobin A1c Is Associated With Increased Risk of Incident Coronary Heart Disease Among Apparently Healthy, Nondiabetic Men and Women,Jennifer K. Pai, Leah E. Cahill, Frank B. Hu, Kathryn M. Rexrode, JoAnn E. Manson, Eric B. Rimm, 2013, http://jaha.ahajournals.org/content/2/2/e000077

- Reference: Hemoglobin A1c, Fasting Glucose, and Cardiovascular Risk in a Population With High Prevalence of Diabetes, Hong Wang, MD, Nawar M. Shara, PHD, Elisa T. Lee, PHD, Richard Devereux, MD, Darren Calhoun, PHD, Giovanni de Simone, MD, Jason G. Umans, MD, PHD, and Barbara V. Howard, PHD, 2011, http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/34/9/1952

- Reference: Elevated Levels of Hemoglobin A1c Are Associated With Cerebral White Matter Disease in Patients With Stroke, Michal Rozanski, Tobias B. Richter, Ulrike Grittner, Matthias Endres, Jochen B. Fiebach, Gerhard J. Jungehulsing, 2014, http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/45/4/1007

- Note: It IS possible to achieve normal blood sugars by strictly following the Dr. Bernstein’s Diabetes Solution. This may not be the only way, but it has worked for me. On the other side of the table (*Personally, I have not had success with this), the Mastering Diabetes diet runs completely contrary to the Dr. Bernstein diet. In spite of this, you can see that the two cofounders of the approach achieve almost normal blood sugars of 5.4% and 6.0%

- Note: Potato MUST be raw. Amazingly, this has almost no effect on my blood glucose. I assume that this is due to the resistant starch. Potatoes are inexpensive, potassium rich, easy to find in the 3rd world, and easy to carry and eat on a bicycle

- Note: Actually, non-diabetic athletes may also have similar blood glucose excursions: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5094325/

Hi Brian,

Great stuff, thanks for sharing your hard won experience. I bikepack and have wondered if you test for ketones when you race. If so what level of ketones do you find acceptable? I had bad ketones during the tour Aotearoa last year but had very ‘good’ flat line BG.

Hi Iain – I’m excited to hear from a fellow T1D bike packer! No, I don’t test for ketones while racing, but I did own a Biosense Ketone meter for several years (in fact, I just sold it today). When I started out eating low carb + exercising, I would find that my ketones could get pretty high on the meter. It only went up to 4.0 mmol/L (actually they use a different unit which is 1:10 so this means the meter read “hi” because 40 is the highest it will read). When my ketones went into the 3.0 mmol/L range and above, I’d have a headache, and a weird taste in my mouth and just feel wiped out. I did low carb (even zero carb) for a many years, and believe it or not, my ketones don’t go that high any more – even if I try to eat zero carb. I used to feel best between 0.4 mmol/L and 1.8 mmol/L. Another thing has changed during that period: I need more insulin for fat than I used to in order to stay at my target of 85 mg/dL. I think that the higher insulin levels may have put a damper on the ketones, which for me is a good thing. I know all those keto people are vying for high ketones, but I don’t see this as an athletic advantage. Recently, I have started eating more and more carbs. At first, I ate carbs during exercise, and as long as I stopped them 1 hour before the end of exercise, they would practically vanish. I decided to add even more carbs from fruit for the last month and I’m finding that it my insulin doses are actually going down and I’m very happy and surprised with the stability. Another oddity is that after all that time on low-carb, my ketones seem to be permanently in the 0.4 mmol/L – 0.8 mmol/L range. I assume you were doing low carb during your Tour Aotearoa? If so, how long had you been doing Low Carb? There is such a thing as “euglycemic ketoacidosis”.. most common in people exercising of course. It can be really dangerous actually because your blood sugar meter makes it look like you’re OK… but if you’re not testing ketones too, you could be in trouble. You may have noticed the comment from Brandon B in this post.. and he pointed me towards “Supersapiens”… a company founded by a T1d (Phil Sutherland), but the target audience is non-D healthy athletes. Phil has gained enormous insight from monitoring blood sugar in healthy athletes – and it’s not the same kind of profile you see from people who are sedentary. I delved into their podcasts and videos, and I’m definitely less afraid of carbs than I used to be! Also, apart from diabetes, I find it really cool you did the TA!! Congratulations on doing that route – it must have been a blast!

Hey Brian- just found these articles, very insightful! Interested to see if you’ve followed the “Supersapiens” project and the very interesting data they’ve found using glucose sensors in non diabetic athletes, including Elite runners hitting BG numbers in the 210-220 range during fast running!

Brandon – Thank you for mentioning this; I just saw it today, but wanted to reply to you. I think that this topic is really fascinating, and I wish there were more data available for athletes – in particular elite athletes. We tend to think that athletes are “healthier,” but if they are having diabetic blood sugars for several hours, that calls into question both our assessment of what is “healthy” as well as the notion that maintaining flat line blood sugar at 83mg/dL is a necessary target. I have read that on-average, Tour de France winners live longer than their non-racing counterparts. That suggests elite level activity could be beneficial for longevity. On the other hand, I’ve also read that keeping your blood sugar particularly low (like in the 70-80mg/dL range as opposed to the 80-100mg/dL range) leads to longevity. Given your reference, these two seem at odds with each other. I’m reading the “supersapiens” page right now. Thanks!